In 2024, 17 items of Asante gold court regalia in the V&A’s collection went on show in Kumasi, the capital of Asante in Ghana, for the first time in over 150 years. The exhibition, Homecoming: Adversity and Commemoration, with the gold at its heart, was opened by Asante King (Asantehene) Otumfuo Osei Tutu II as part of his silver jubilee celebrations in the newly re-opened Manhyia Palace Museum.

Asante gold court regalia in the V&A collection. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

These items, including a gold peace pipe (abua) and four cast gold soulwashers’ badges (akrafokonmu) used by high-ranking officials to purify the King’s soul, demonstrate historic gold-casting techniques for which the Asante are renowned. Beaten gold ornaments with intricate and symbolic decoration that once adorned thrones, canopies and swords also went on show, along with a small cast gold eagle and a cast gold ring. The gold regalia is decorated with patterns and motifs that express loyalty, honesty, cultural bonds and family mottos, giving it meaning far beyond its material value. Its powerful spiritual and cultural significance is deeply embedded in Asante identity. At the exhibition unveiling, the Asantehene described the regalia as “the soul of the people of Asante”.

Peace pipe (Abua), before 1874, Asante. Museum no. 368:1 to 8-1874. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

(Left to Right:) Soulwasher’s badge (Akrafokonmu), before 1874, Asante. Museum no. 370-1874; Ornament, before 1874, Asante. Museum no. 373-1874. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

The historic gold regalia also symbolises trauma. The 17 items from the V&A were among several hundred pieces looted by British troops from the royal palace in Kumasi on 4 February 1874 during the Anglo-Asante Wars of the 19th century. Many were later sold at auction and dispersed among museums and private collectors. The regalia is therefore indelibly linked with British imperial history in West Africa and, today, makes up one of the V&A’s most sharply-spotlit collections given the focus of museums around the world on decolonisation and provenance research. When the gold arrived in Kumasi, Ivor Agyeman-Duah, the Asantehene’s cultural advisor and Director of the Manhyia Palace Museum, described how, “The emotions that came out of the Asantehene when he first saw these objects … underlined the whole history of the 19th century”.

The significance of gold to the Asante

Since the foundation of the Asante empire during the late 17th century, gold has been central to Asante identity and economic stability. Asante kings grew powerful on local gold deposits and the palace in Kumasi became the focal point for a lucrative international gold trade. The gold regalia is the ultimate symbol of Asante royal government: it embellishes the royal throne, is worn by high-ranking court officials and, above all, is worn by the Asantehene, who is adorned with gold ornaments at royal ceremonies.

The most revered item in the regalia is the golden stool, which in Asante tradition, descended from heaven and was received by a priest, Okomfo Anokye, who presented it to the first Asantehene, Osei Tutu I. Possession of the golden stool is vital to the survival of the Asante kingdom and attempts by Britain to obtain the stool during the 19th century were strongly resisted. Not even the Asantehene is allowed to sit on the golden stool, which contains the spirits of previous Asante kings. A powerfully-expressive statue of Okomfo Anokye receiving the golden stool stands on a major intersection on the border of Adum and Bantama in Kumasi, near to the site of the old royal palace.

Early European visitors to Kumasi were dazzled by the court of the Asantehene. In 1817, the English writer and diplomat, Thomas Bowdich, described meeting the Asantehene when he was sent from Cape Coast Castle (a former British gold, spice and slave trading post on the West African coast) to negotiate a trade treaty:

The sun was reflected, with a glare scarcely more supportable than the heat, from the massy gold ornaments, which glistened in every direction. … Under the next umbrella is the royal stool, thickly cased in gold. Gold pipes, fans of ostrich wing feathers, captains seated with gold swords, wolves heads and snakes as large as life of the same metal, depending from the handles, girls bearing silver bowls, bodyguards, &c. &c. are mingled together till we come to the King, seated in a chair of ebony and gold.

Thomas Bowdich, 1817

The gold casting process

Bowdich was shown the traditional Asante methods of lost-wax casting in gold used to produce items like this soulwashers’ badges. He described the making of a gold ring:

Bees wax for making the model of the article wanted, is spun out on a smooth block of wood, by the side of a fire, on which stands a pot of water; a flat stick is dipped into this, with which the wax is made of a proper softness; it takes about a quarter of an hour to make enough for a ring. When the model is finished, it is enclosed in a composition of wet clay and charcoal (which being closely pressed around it forms a mould) dried in the sun, and having a small cup of the same materials attached to it (to contain the gold for fusion) communicating with the model by a small perforation. When the whole model is finished, and the gold carefully enclosed in the cup, it is put in a charcoal fire with the cup undermost. When the gold is supposed to be fused, the cup is turned uppermost, that it may run into the place of the melted wax; when cool the clay is broken, and if the article is not perfect it goes through the whole process again. To give the gold its proper colour, they put a layer of finely ground red ochre (which they call Inchuma) all over it, and immerse it in boiling water mixed with the same substance and a little salt; after it has boiled half an hour, it is taken out and thoroughly cleansed from any clay that may adhere to it.

Ring, probably before 1874, Asante. Museum no. M.256-1921. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

The same technique is practised today by the royal goldsmiths. In 2025, the V&A acquired a cast gold ‘scorpion’ ring by Asante royal goldsmith, Nana Poku Amponsah Dwumfour. He was enstooled (installed as chief) as Buramuhene (Chief of the Furnace in the Akan dialect Twi) in 1990 and still practises in the workshop used by his ancestors centuries ago.

The Anglo-Asante Wars of the 19th century

The regalia in the V&A collection was looted from the palace during the third Anglo-Asante War of 1874. By that time, Britain and the Asante had long been trading partners. From the late 17th century, European powers, most notably Britain and the Netherlands, began supplying the newly established kingdom of Asante with weapons, metals and luxury goods in exchange for enslaved people, gold and spices. The enslaved people were shipped across the Atlantic to work the plantations and mines whose products were sent back to Europe for conversion to luxury goods as part of the triangular trade. Europeans had rarely ventured inland since the Portuguese first built St. George’s Castle in the trading port of Elmina in the 1470s and still today, dotted along the coast, are the remains of nearly 100 forts, lookouts and staging posts from where the Portuguese, Dutch, Danish, Swedish and British had based their activities.

The parliamentary abolition of the slave trade in 1807 tightened Britain’s focus on gold trading and over the next 60 years Britain became increasingly dominant over claims to the coastal forts as other European powers withdrew their interest. When the Dutch ceded control of Elmina in 1870 – 71, Britain secured almost total control over a 300-mile stretch of coastline. Although Elmina was in Fante territory, the Asante had claimed long-held rights to the port. Britain did not honour the agreement the Asante had with the Dutch and so the Asante launched an attack against the British garrison in the castle.

Under the leadership of Major-General Sir Garnet Joseph Wolseley, the British sent three ships to West Africa in late 1873. The conflict that followed is known in Ghana as the Sagrenti War after the local pronunciation of Sir Garnet. In January 1874, British troops set foot on land about eight miles east of Elmina near Cape Coast Castle, by then, the centre of British administration along the coast. Engineers cut roads, set up telegraph cables and built bridges as a first wave began marching the 100 miles inland towards the Asante capital. They reached Kumasi on 4th February.

Faced with overwhelming odds and the impossible demand for an indemnity of 50,000 ounces of gold, the Asantehene, Kofi Karikari, fled. Wolseley ordered troops to gather as much of the royal regalia as possible and then destroy the royal palace.

The ‘punitive raid’ and the media

In Victorian Britain, the attack on Kumasi was seen as a ‘punitive raid’ to exact reprisals against the Asante King. ‘Punitive’ is a term loaded with imperial entitlement. Punitive expeditions were characterised by responses that were often out of proportion to the perceived provocation. Their purpose was twofold. They aimed to remove all possibility of future interference in Britain’s imperial and commercial interests overseas by weakening or removing the governments of communities who resisted British encroachment. They also sent a message to other countries around the world – in particular rival European powers – that wherever in the world Britain’s interests were challenged, Britain had the power to respond.

An important aspect of the punitive raid was the use of broadcast media. Correspondents and photographers joined traditional war artists in describing events to a growing readership as general literacy levels increased in the second half of the 19th century. British newspapers presented a narrative based around sovereignty, liberation and progress. The writer and explorer, Henry Morton Stanley, accompanied the expedition to Kumasi and wrote up his accounts for both the New York Herald and the Daily Telegraph. Later in 1874, he published Coomassie and Magdala: the Story of Two British Campaigns in Africa outlining his experiences both on the Asante expedition and on another punitive raid from which the South Kensington Museum (now V&A) acquired looted artworks, that of Maqdala, Ethiopia, in 1868.

Soldiers were also becoming more literate, sending letters home to Britain from the frontline and recording their experiences in diaries and journals. A first-hand account of the raid from the perspective of a British rifleman is available in the V&A’s National Art Library in the form of a ‘Diary of the Ashantee War by an Eye Witness from 1873 to 1874, by A/C George Little, 2nd Batt. Rifle Brigade, Gibraltar, 1875’. Written in the language of a late 19th-century foot soldier, the diary is a troubling read to modern audiences. George Little witnessed the looting of Kumasi by British troops – although he did not see the gold – and he took part in the burning of the royal palace.

The diary, therefore, positions Little at the centre of the two most political aspects of any imperialist ‘punitive’ raid. The theft of the royal regalia removed the symbols of office, denying the Asante king the right to govern. Destroying the palace in Kumasi eliminated the historical seat of power. In Stanley’s report of the British attack on Kumasi and subsequent looting of the regalia, he published reports by Wolseley to the Secretary of State for the Colonies that included the phrase, ‘I had shown the power of England’.

Military looting

Looting is another term that needs explaining in a 19th-century British military context. Today the term suggests uncontrolled violence and a chaotic free-for-all but for a military expedition, this would suggest a breakdown in discipline. Unauthorised looting was punished severely. The looting took place after the violence and was a carefully-orchestrated administrative procedure by officials equipped with clipboards, rather than guns. This formalised process of looting – referred to at the time as the gathering of ‘prize’ – was official War Office and army practice.

In Kumasi, Wolseley appointed three ‘prize agents’ to gather the most valuable materials so that they could be sold. The proceeds went partly towards paying for the expedition. The rich Kente cloths and other items of great value in West Africa were auctioned at Cape Coast Castle. The gold was taken back to Britain for sale, where it could fetch much higher prices.

The Asante gold in Britain

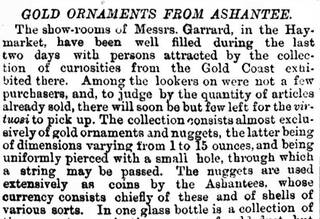

The gold regalia was sold at Garrard’s, the Crown Jewellers, in April 1874. They had paid £11,000 for hundreds of items that they sold on the open market. Although records of the sale were lost during the Second World War, newspaper reports show a British public enthused with a mixture of excitement, curiosity and imperialist triumphalism.

On 30 April, The Globe published an article titled, ‘Gold Ornaments from the Ashantee’ that claimed, ‘The show-rooms of Messrs. Garrard, in the Haymarket, have been well filled during the last two days with persons attracted by the collection of curiosities from the Gold Coast exhibited there. Among the lookers on were not a few purchasers and, to judge by the quantity of articles already sold, there will soon be but few left for the virtuosi to pick up’.

The display also caused a moment of reflection when the skills of the Asante goldsmiths became apparent: ‘The most extraordinary fact is that, with one or two exceptions, the whole of these ornaments are cast, and not wrought or hammered. The most elaborate devices – and some of them are extremely elaborate – appear to have been traced wholly on the clay cast, and in very few instances has anything been added to the work when once it has come from the caster’s hands. … The English jewellers are not above owning that they may take some hints in casting from the Ashantee workmen, some of whose designs are, as they frankly admit, clever enough to baffle their conjectures as to how they were executed. ‘Fas est et ab hoste doceri,’ [‘It is right to learn even from an enemy’] but we hardly expected to gain by our expedition against King Coffee [sic] a lesson in the art of gold-casting.’

Asante gold in South Kensington

The V&A (then the South Kensington Museum) acquired 13 pieces at the sale and bought two further items within a decade, one section of sheet-gold ornament purchased in 1874 from a military family and one cast gold soul-washer’s badge, purchased in 1883 with no record of the previous owner. A gold ring given to the museum by an artist in 1921 and a gold ornament in the form of an eagle given by a private donor in 1936, most likely came from the regalia.

Of the hundreds of items of gold regalia looted from Kumasi in 1874, the museum selected pieces that were exemplars of Asante goldsmithing techniques and displayed them for British artists and designers seeking inspiration for new work. While we know the purpose of most of the cast pieces, the original locations of many of the beaten gold ornaments were not recorded. As they were removed, they became decontextualised from their original roles and when they came to the museum, they were recontextualised as abstract ornaments for designers. Some have torn edges, suggesting they were removed in a hurry. The gold regalia was complemented later by electrotype reproductions from other collections that were toured around design schools and art colleges.

Ornament, before 1874, Asante. Museum no. 374-1874. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

A week after the sale, the museum also bought two further items of jewellery and a copper-alloy goldweight from a Serjeant Pearce who either looted them himself without permission, or bought them at one of the sales. These were not requested for return to Manhyia Palace in 2024.

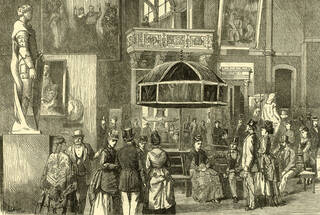

Soon after the sale in April 1874, the exhibition, ‘A Collection of Gold and other objects from Ashanti at the South Kensington Museum‘ opened to the great interest of the popular press. Their illustrations depicted the former Asantehene Kofi Karikari’s state umbrella in the centre of the room. Items from the Asante regalia reached an even bigger audience when they were shown again in 1886 at the Colonial and Indian Exhibition on the site of what is now the Natural History Museum. The exhibition was conceived as a successor to the Great Exhibition of 1851 but whereas that championed industrial competition between European powers, this was more a demonstration of the power and reach of the British empire only a few years after Queen Victoria had been crowned Empress of India. It was visited by over five million people.

A renewable cultural partnership

The raid on Kumasi was one of the key events in the Anglo-Asante Wars of the 19th century that resulted in Britain claiming Asante and neighbouring territories in 1901 as The Gold Coast Colony. In 1896, Britain exiled Asantehene Prempeh I to the Seychelles and on his return in 1925, a new palace in Kumasi was built by the British as a gift. To assert independence, the Asante refused to accept this as a gift and paid for it in gold. It is this building that is now the Manhyia Palace Museum. Britain only recognised Prempeh I as King of Kumasi. It was not until 1935 that Prempeh II was enstooled as Asantehene. In 1957, Ghana, as a country of separate communities linked by a single border, became the first African nation south of the Sahara to gain independence from Britain.

The spiritual significance of the Asante gold and the trauma associated with its looting mean, therefore, that the raid on Kumasi in 1874 was an attack on Asante identity that is still felt to this day. Modern approaches to objects acquired during conflict mean these items joined the museum’s collection in ways that would not be acceptable now.

In 2023, during an official visit to London, Asantehene Otumfuo Osei Tutu II requested that both the British Museum and the V&A should return the historic regalia. A tripartite agreement was established between Manhyia Palace Museum, the V&A and the British Museum that has enabled the return to Kumasi of 17 items from the V&A and 15 from the British Museum on loan. Seven pieces formerly in the Fowler Museum, California were fully restituted at the same time.

(Left to Right:) Sheena Ofori; Teddy Kyei-Poku and Loretta Gyasi, 30 April 2024, Manhyia Palace Museum. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

The V&A items are on loan for periods of three years at a time, with the option to extend, subject to approval from Arts Council England. For national museums like the V&A to lend items known to have been looted during colonial conflicts is a contentious issue and we are often asked why we do not simply transfer legal ownership. The National Heritage Act of 1983, under which we are governed, only allows us to remove items from the collection in very narrow circumstances. There is no power under the Act for the V&A to return items because they were acquired through imperial conflict.

The Act, however, does not mean we sit back and do nothing. We take seriously our responsibility to share collections as widely as possible. The V&A has a very active international programme for both short- and long-term object loans. The loan of the Asante gold follows similar administrative arrangements to our other international loans, but in collaboration with Manhyia Palace Museum, we have developed this into much more than a simple transaction. Our Renewable Cultural Partnership is based around exchanges of knowledge and skills. V&A and British Museum staff contributed to the installation of the exhibition, and in response to a request from Ivor Agyeman-Duah, have supported Manhyia Palace Museum staff in object transport, presentation, environmental control, gallery text writing and storage. Manhyia Palace Museum colleagues have taught us more about the items in the collections, bringing new insights into the meanings behind each piece. For Agyeman-Duah, the return of the gold to Kumasi represents, “an important step in the process of acknowledgement, reconciliation and healing between the UK and Ghana and a recognition of the lasting cultural, historical and spiritual significance of these objects to the Asante people”.

‘Unity’, designed and made by Nana Poku Amponsah Dwumfour, Amankwaa Opoku Benjamin and Emefa Cole, 2025, London, England, and Kumasi, Ghana. Museum no. M.27-2025. Museum no. null. Commission supported by the V&A Americas Foundation. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Collaboration is ongoing. In October 2025, the V&A acquired a new sculpture as part of the Renewable Cultural Partnership. Unity is a collaboration between the Asante royal goldsmith, Nana Poku Amponsah Dwumfour, his son Amankwaa Opoku Benjamin and British-Ghanaian goldsmith-jeweller, Emefa Cole that brings a piece of Asante goldsmithing into the V&A’s collection that has a clean provenance from the goldmine to the display case. The sculpture in gold, bronze and silver, was inspired by the historic Asante gold now in the Manhyia Palace Museum, but was driven by the need to expand the range of the museum’s contemporary collecting and to offer a forward-looking call to promote a spirit of friendship. The sculpture represents a proverb chosen by the royal goldsmith: ‘When two sides come together, it becomes complete’.