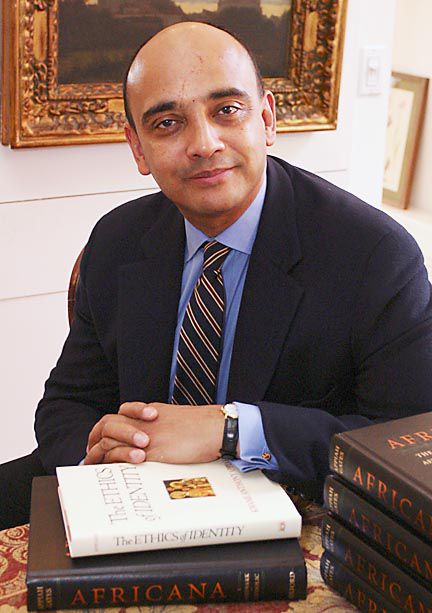

Kwame Anthony Appiah

I think I know why I was asked to speak today. It’s because my sisters and I are the fruits of a long-term successful Anglo-Asante collaboration, namely the marriage between my English mother and my Asante father. But the family connections run much further back. As you know, Nana Prempeh the First was exiled to the Seychelles after Asante became a Crown Colony. Well, the British cabinet that approved the return of Nana Prempeh I to Asante in 1924, included my great-grandfather, Lord Parmoor. But the connections don’t end there: because when my Asante grandfather’s brother-in-law, Nana Prempeh II, became Kumasihene in 1931, his appointment required the consent of the Secretary of State for the Colonies, who happened to be my great-great Uncle, Lord Passfield.

In this room today another family is represented whose ancestor was an important figure in the history of constructive connections between England and Asante: because Thomas Edward Bowdich, whose descendants are with us here, visited the Asantehene Nana Osei Bonsu in 1817 and 1818, bringing back a treaty of “perpetual peace and harmony” for Anglo-Asante relations on the Gold Coast; and his book Mission from Cape Coast Castle to Ashantee is one of the earliest extended accounts by a European of life at the Asante court.

People sometimes focus on the five Anglo-Asante wars of the nineteenth century. But between the end of the first, which settled the southern boundary of Asante at the Pra River in 1831, and the beginning of the second, in 1863, were three decades of peace. Still, one thing we acknowledge today is the first, and the only unhappy anniversary of the three that we are recognizing, which occurred in the third of these wars. For this year is the 150th anniversary of the ending of the third Anglo-Asante war, in 1874, with the sacking of Kumasi by Sir Garnet Wolseley, who entered the capital unopposed, and committed a series of what would now be thought of as war crimes. Among the objects of his destructive campaign was a large stone building in the city’s center, the Aban that Nana Osei Bonsu had created, inspired by talk of the British Museum.

As Wolseley prepared to loot and blow up the Aban, European and American journalists were allowed to wander through it. The Daily Telegraph described it as “the museum, for museum it should be called, where the art treasures of the monarchy were stored.”The London Times spoke of “Books in many languages, Bohemian glass, clocks, silver plate, old furniture, Persian rugs, Kidderminster carpets, pictures and engravings, numberless chests and coffers …” The New York Herald augmented that list: “scimitars of Arabic make, Damask bed-curtains and counterpanes, English engravings, an oil painting of a gentleman, an old uniform of a West Indian soldier, brass blunderbusses, prints from illustrated newspapers, and, among much else, copies of the London Times ….” Some of what is now returning was taken then.

But let’s turn to the second, entirely joyful, anniversary we record today, which is the centenary of the return of Nana Prempeh I from textile in the Seychelles to Kumasi, authorized, you’ll recall, by a British government that included my great-grandfather.

That return initiated a period of peace and progress in Asante that continues to this day. My sisters and I grew up in the Kumasi of Nana Prempeh II. One of my happiest childhood memories is going up to the palace after church on Sundays, to sit with my mother on a veranda shaded with vines, and wait for Nana Prempeh to come out and sit with us for a while. Our meetings took place in the modest building the British had allowed Asante to build in the old palace grounds when the monarchy was restored after his predecessor’s return from exile, a building that was replaced with a new modern palace after my father’s brother-in-law, Otumfuo Nana Poku Ware II, succeeded Nana Prempeh as Asantehene. That building is now home to the museum whose contents will be enriched by the return of many objects from this museum and the V&A, which we are here to celebrate today. We should all be grateful to Ivor Agyeman-Duah and Professor Malcolm McLeod, old friend of Asante and once Keeper of Ethnography here at the British Museum, for successfully negotiating this happy outcome.

The Kumasi of Nana Prempeh II was a wonderfully cosmopolitan city. There were people there from all our regions, speaking all the languages of Ghana. Our main commercial thoroughfare was called Kingsway Street, but is now Prempeh II Avenue. In the 1960’s, if you wandered down it toward the railway yards at the center of town, you’d first pass by Baboo’s Bazaar, which was run by a charming and courteous Indian. I remember, too, that we got our rice from Irani Brothers; and we often stopped in on various Lebanese and Syrian families, and even a philosophical Druze, named Mr. Hani, who sold imported cloth, and was always ready, for a conversation about the troubles of his native Lebanon.

There were other “strangers” among us, too. In the military barracks in the middle of town you could find many Northerners, faces etched in distinctive patterns of ethnic scarification. And then there were Europeans: a Greek architect, a Hungarian artist, an Irish doctor, a Scottish engineer, a French lady who taught us her language, English barristers and judges, and a wildly international assortment of professors at the university from every continent. Kumasi grew from war; but it has flourished now with so many years of peace. It’s university, built on land given to it by Nana Prempeh II, on whose campus I went to primary school, is now one of the great scientific universities of Africa. So, I would like to thank Asante, through her king, for the pleasure and privilege of having grown up in that wonderful city.

And, indeed, the third and most joyful anniversary we celebrate today is the silver jubilee of your installation, Sir, as the sixteenth Asantehene. Your late mother, the magnificent Queen Mother of Asante, was one of my mother’s very good friends. Whenever we visited her, my mother would greet her in a very English way with a kiss on the cheek, and so your mother used to joke when my mother arrived, “Me kunu aba”—My husband has arrived! So, I heard talk of you, Sir, from your proud mother long before you ascended the Golden Stool.

It would take too long even to summarize the many achievements of your reign, but you have done so much to modernize a centuries-old kingdom, while keeping faithful to her traditions. And I’d like to end, if you will permit me, Sir, by picking out just three representative achievements that reflect the way you have continued our traditions while modernizing the monarchy.

First, your commitment to securing the natural environment. Lake Bosomtwe is one of the most extraordinary elements of the Asante landscape, a meteoric crater that has filled with water over the million years since it was created by an asteroid. No rivers enter or leave the lake, so over the ages rain has brought water and evaporation has taken it, to produce a lake with a unique combination of salts and a unique set of fish. You, Sir, have led a project to plant two and a half million trees around the lake; a place I know well because my father’s parliamentary constituency in the 1950s was on its shores.

A second emblematic achievement of your reign has been the creation of the Otumfuo Osei Tutu II Charity Foundation that focusses on two themes of your administration: the education of Asante’s children, our most precious asset, and the health of its people.

But finally, Sir, we should esteem you for your commitment to the process we are participating in today: the determined concern to honor Asante’s extraordinary cultural heritage.

Ladies and Gentlemen, Nananom, please welcome His Royal Majesty Otumfuo Nana Osei Tutu Ababio, the sixteenth Asantehene.

[This introductory lecture was delivered at the Batish Museum by the eminent philosopher, Kwame Anthony Appiah currently of the New York University and President of the America Academy of Arts and Letters. This was before the Asantehene Otumfuo Osei Tutu II delivered his lecture on Asante Culture Past and Present at the British Museum on July .19 at the BP Lecture Theatre].]